My volume provides the first complete English translation/paraphrase of the work. It also includes my interpretive essay about certain points, something that was first published in Spiritual Life magazine.

I include here a passage from that essay. I think the point stands alone without elaborating further on the context. Of all my books, by the way, this is undoubtedly the most difficult to follow for those unfamiliar with life in monasteries and convents.

---------------------------------

Gratian

then adds a short but rich section entitled, “Brief, Clear and Certain Plan for

Attaining the Height of Perfection”:

Devote yourself to being very humble and love God tenderly.

Devote yourself to being very humble and love God tenderly.

And

put that person who has hurt you the most, whether inside or outside the

convent,

In

your heart and together with the Heart of Christ love that one greatly.

Let

this be the first person you pray for.

Ask

nothing good for yourself that you do not first ask for the other.

Make

many acts and promises to God that if for the glory and honor of God,

it

were necessary for you to lose honor, health, and life, and even your own glory

for

the honor, health, and life, and even glory of that person,

then

you are determined to give all that good.

By

making these promises and desires often and continually kissing their feet

interiorly

and

even the ground on which they walk,

and

orienting allyour acts and resolutions

in prayer,

you

will by this single road rise to the highest grade of perfection and attain heroic

virtue…

In the mythical meeting that provides the context of these remarks, the members of the gathering assure one another that no one could possibly understand such doctrine. It does seem quite exalted, for all its apparent simplicity. Readers might be tempted to respond in the words of those followers of Jesus who were unsettled by the Bread of Life discourse presented in John 6, “This sort of talk is hard to endure! How can anyone take it seriously?”

Yet is this advice so far beyond the ordinary person?

A

personal testimony

When

I entered the Discalced Carmelite novitiate at Marylake outside Little Rock in

1972, I

had

a classmate who had the faculty of displeasing me in everything. He was a fine

and talented man, and I imagine no small part of my difficulty was envy of his

creative nature. It was

not

long before I found my prayer life taken up largely with complaining to God

about him.

At

some point I stumbled across the idea contained in Gratian’s text, although I

don’t recall where or how. Every night after the community completed Night Prayer

and the others returned to their cells for the evening, I stayed behind and

prayed for a while for my companion. I prayed that he do well, that he be filled

with blessings, that his struggles be lightened. In a matter of a week and a

half, I no longer was filled with resentment towards him. When he chose to

leave the community a few months later, although I agreed with his decision, I

was sad to see him go.

A

corporate witness

This

approach to dealing with resentments and interpersonal difficulties is

well-known to people in Twelve Step programs. In a chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous, significantly

titled “Freedom from Bondage”, the reader is advised that the way to move

beyond resentments is to pray

for

the person resented, asking for everything that one would want for oneself. The

author asserts that within a very short time, one will discover that resentment

and bitterness will have been replaced by love and compassion.

In Twelve Step meetings around the world, men and women who have struggled with the destructive power of addictions bear witness to the power of this approach. They will be the first to tell you they are not saints. Yet in this, they are following a clear and certain path to the heights.

For what is the height of perfection if it is not compassionate understanding and love?

In Twelve Step meetings around the world, men and women who have struggled with the destructive power of addictions bear witness to the power of this approach. They will be the first to tell you they are not saints. Yet in this, they are following a clear and certain path to the heights.

For what is the height of perfection if it is not compassionate understanding and love?

------------------

To

read about the Twelve Step advice in context, see Alcoholics

Anonymous Fourth Edition (New York City: Alcoholics Anonymous World

Services, 2001) 552.

-----------------

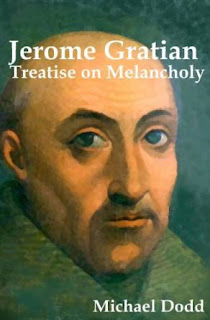

A further note: Tom did the cover design, basing it on an old portrait of Gratian. The publications director of ICS Publications liked it so much that she asked permission to use the image in the cover design for a translation of Gratian's lengthy autobiographical materials that they will publish, I hope, in the near future. I assisted in a small way with the editing of that volume, too.

1 comment:

this was splendid. thank you for this.

Post a Comment